Early Identification of Sick Dairy Calves Important to Their Survival and Future Milk Production

Early Identification of Sick Dairy Calves Important to Their Survival and Future Milk Production

Introduction

The health of dairy calves early in life (their first 8 weeks) directly impacts future milk production and longevity in the dairy herd. Protecting the future health and survivability of calves starts with timely feeding of adequate amounts of high-quality colostrum (see section below for key points) and disinfecting the navel with 7% tincture of iodine or a chlorhexidine solution. In addition, dairy calf managers must be able to identify sick calves and provide supportive therapy early for the best survival rates and to minimize effects on long-term productivity.

In multiple National Animal Health Monitoring Surveys, dairy producers and their veterinarians indicated that scours (diarrhea) occurred in 24% of dairy calves prior to weaning and that 12% of calves had respiratory issues (pneumonia). Scientists have indicated that incidence rates of pneumonia are much higher than indicated by producers and are often go undetected.

The highest risk for scours occurs within the first month of life. Young dairy calves with scours can become severely dehydrated quickly. If they are not treated in a timely manner, their chances of survival can decrease tremendously. Respiratory issues more often are seen when calves are stressed particularly around weaning time. However, the first episode may be traced to the pre-weaning period.

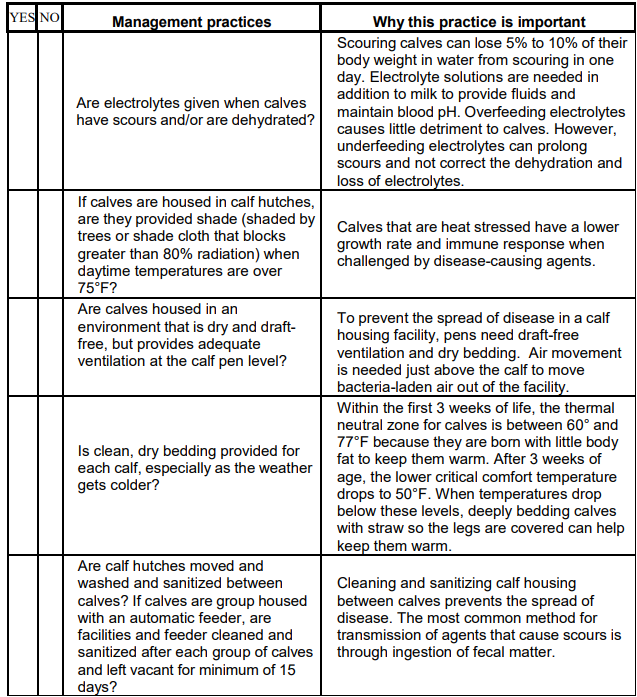

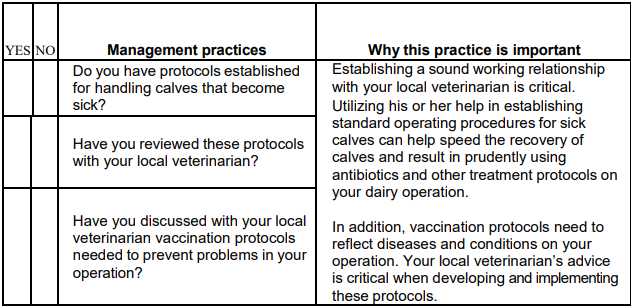

Excellent dairy calf managers can spot diseases early and treat these calves so they have the best chances of recovering quickly. To help train employees and family members to detect illnesses in dairy calves, we provide a check sheet with common symptoms to evaluate. Once sick calves have been identified and more closely examined, protocols developed with your local veterinarian should be implemented to treat these calves. In addition, reviewing management practices and instituting changes can help prevent illnesses in young dairy calves.

Critical Control Points for Colostrum Management

- Feed colostrum within 6 hours of birth. Absorption of antibodies decreases with age and is essentially non-existent by 24 hours of age.

- Hand-feed an adequate amount of colostrum –- 4 quarts to Holsteins; 3 quarts for Jerseys. Studies have shown that first lactation milk yields are higher in calves fed 4 quarts versus 2 quarts of colostrum at birth.

- Feed high-quality colostrum where quality has been measured (i.e., with a colostrometer or Brix refractometer where reading is greater than 22%)) and feed to provide a total of 100-150 g IgG.

- Make sure bacteria counts are low in colostrum. Milk colostrum into a clean bucket from cows prepped for milking. Feed colostrum within 1 hour of collection, or refrigerate or freeze it immediately upon collection. Use clean plastic bottles filled with frozen water to lower the temperature of colostrum at harvest before/while being refrigerated or frozen.

- Remove calves from dams at birth to avoid suckling around legs and brisket, which can result in the consumption of manure.

Identifying Potentially Sick Calves

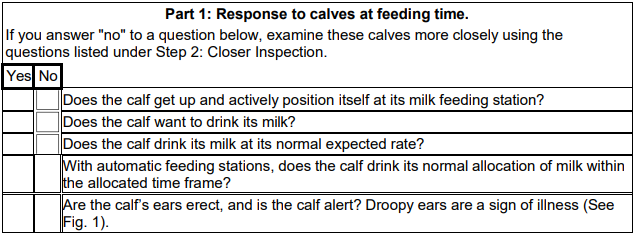

Step 1: Identify calves needing more careful evaluation at and just before feeding times.

Figure 1. An alert calf with erect ears.

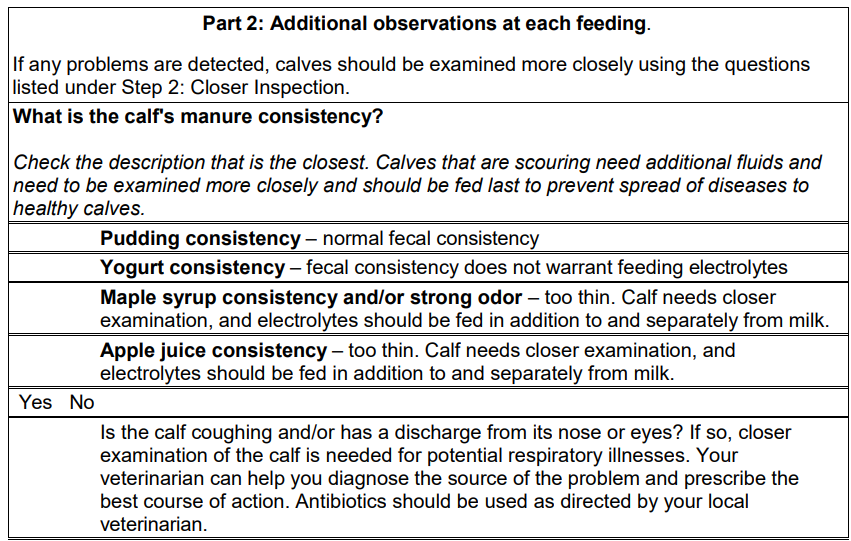

Figure 2. Everting a calf's lower eyelid

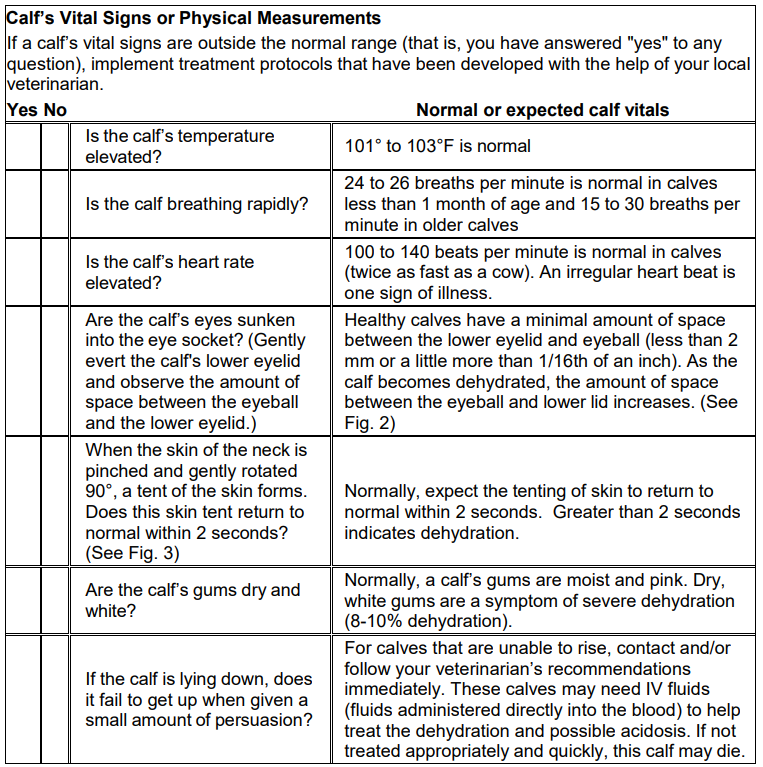

Step 2: Closer Inspection (for calves with potential illness detected through questions answered in Step 1)

Figure 3. Performing a "skin tent" test. On a healthy calf, the skin should return to normal within 2 seconds.

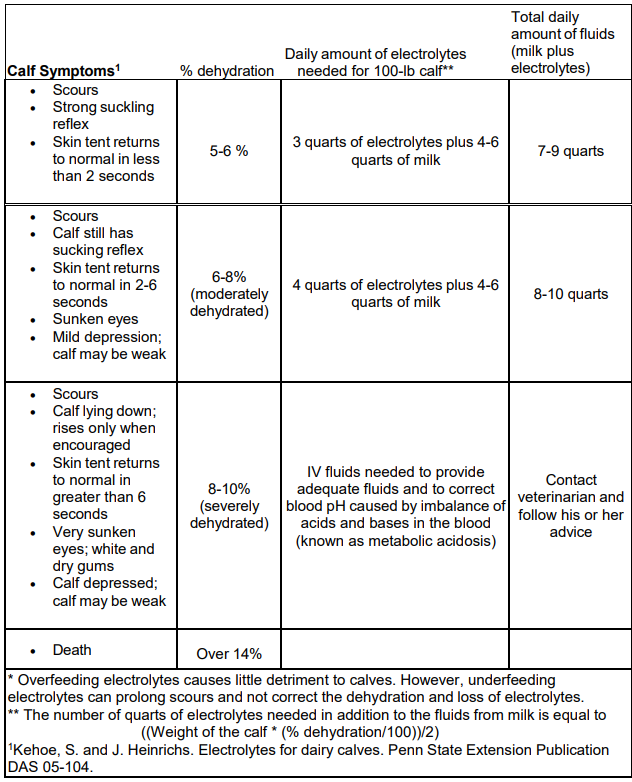

Electrolytes Important for Scouring Calves

Calves can lose 5% to 10% of their body weight daily in fluids due to scours. To replace these lost fluids, electrolytes should be fed in addition and separately to the calf’s allocation of milk. Electrolytes alone do not provide an adequate amount of energy for the calf to fight off the disease and maintain body weight. To determine if additional treatments (i.e., antibiotics) are needed to help the calf recover from scours or pneumonia, farmers should work with their local veterinarian to develop treatment protocols that reflect the needs and diseases seen on their dairy operation (known as standard operating procedures, or SOP).

Author: Donna M. Amaral-Phillips